Canadians know about the Underground Railway, the network by which escaped slaves in the U.S. could cross the border and find freedom in Canada. But not as well known is the fact that slavery existed in Canada for decades, before the institution was outlawed by the Imperial Government in London in 1834. August is Emancipation Month, marking that very significant act by the British Parliament, and a good time to look back at slavery in Canada.

After the American Revolution, many of the Loyalists who were forced to remove to the colony of Quebec brought their slaves with them. When Quebec was divided into Lower and Upper Canada in 1791, fifteen of the members of the new Legislative Assembly, the Parliament of the new province, were slave-owners, and the slave trade continued in Upper Canada as men, women and children were bought and sold in what is now Ontario.

Slavery had a long history in British colonies, and had existed in New France before the Conquest. In fact, the Articles of Capitulation, under which New France surrendered to the British forces in 1760 contained an article guaranteeing the continuation in slavery; all those “of both sexes shall remain, in their quality of slaves, in the possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong: they shall be at liberty to keep them in their service in the colony or sell them…”

The first Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe, had led Loyalist militia during the American Revolution, but was personally strongly opposed to slavery. However, many members of his administration were not. Peter Russell, the Receiver General of Upper Canada, and his sister Elizabeth owned slaves. Russell acted for Simcoe after the Governor returned to England in 1796. William Jarvis was the Provincial Secretary of Upper Canada, and his family became one of the leading members of the Family Compact in later years. He was a slave-owner.

Matthew Elliot, a Loyalist who came from Virginia during the American Revolution, probably had as many as sixty slaves living in the huts behind his home in Amherstburg. Even some of the Anglican clergy had slaves, and seemed not to question the morality of slavery. The Reverend John Stuart from Kingston, an Anglican minister, expressed surprise when one of his slaves, a “negro boy”, ran away despite the winter weather in which he escaped. Even some aboriginal leaders owned slaves. The Mohawk leader, Joseph Brant, who settled with his people on the Grand River after the Revolution, probably owned over thirty slaves. But many indigenous people were themselves kept as slaves.

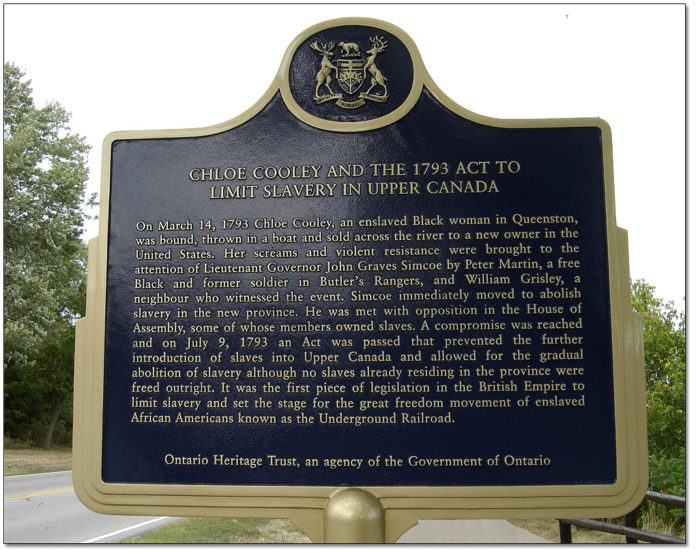

A dreadful event in 1793 finally gave Simcoe an opportunity to act against slavery in Upper Canada. In March of that year, a black slave living in Queenston, was sold to a man in the United States. Chloe Cooley resisted vigorously, screaming and kicking out at her captors, who had her tied and forcibly carried onto a boat that brought her across to the States. The man who had sold her, named Vrooman, was reported to the authorities, but, as one writer put it: “Chloe Cooley had no rights which Vrooman was bound to respect: and it was no more a breach of the peace than if he had been dealing with his heifer.”

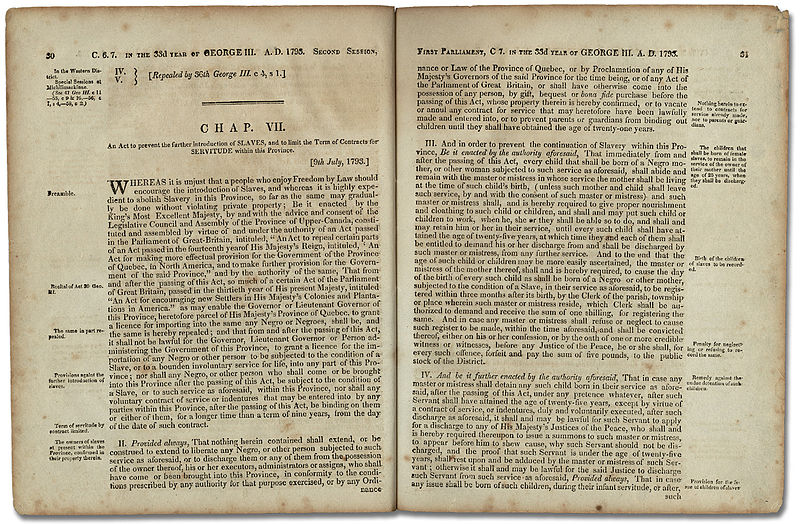

However, the case was brought to the attention of Simcoe who decided to introduce legislation to outlaw slavery in Upper Canada. This met with resistance from the slave-owning members of the Legislature and Simcoe’s Executive Council, and a compromise was reached. On July 9, 1793, 33 Geo. III, c. 7 (U. C.) “An Act to prevent the further introduction of slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude within this province” was passed. This did not abolish slavery completely. All individuals then enslaved remained so for the rest of their lives. Their living children would gain their freedom when they reached the age of 25; but all children subsequently born to slaves would be considered free from birth. No slaves could enter the province: any slaves brought into Upper Canada would be freed automatically. Owners of freed slaves had to provide for their security. This last requirement depended largely on the generosity of the slave’s owner at the time. Some provided homes and financial support for their emancipated slaves. Others actually sold their slaves in the U.S. before the Act was passed, so as not to suffer any financial loss from the legislation.

Nevertheless, in 1798, a Bill was passed by the Assembly in Upper Canada that would have allowed slave owners entering from the United States to keep their slaves in spite of the law. The Bill only died when the legislative session ended, but there was still, clearly a pro-slavery element in Upper Canada by the end of the century.

Simcoe’s Act of 1793 was the first piece of legislation in the British Empire that limited the slave trade or slave-holding. The Imperial Parliament outlawed the slave trade in 1807, and abolished slavery throughout the Empire in 1833. This law came into effect on August 1, 1834. It was not until then that some of the surviving slaves in Upper Canada gained their freedom.