by Susan Peters, Dundas County Archives

There is no doubt that the Brown murders of 1879 were a tragedy for the family and for the community. After submitting my piece about the case, I had felt that this would have been the end of the story. Such was not the case. A couple of days later, the North Dundas Times office received a call from an individual in Winchester. What happened next certainly got my attention. The caller said he had found the original trial transcripts in a sealed envelope hidden between two walls in his home. He was willingly donating them to the Dundas County Archives.

As an archivist, one is often offered a donation of documents from estates. Sometimes, people have met me in the grocery store with an offer of an old newspaper that was found in an attic. I have found items left at my doorstep. This is not ideal, as there is a process of determining if the donation meets the protocols. This includes a determination of whether the items fulfill the collection criteria. Namely, does the material tell the story of Dundas County, or some aspect of it. The next step is to accept the donation with a deed of gift, which Identifies that it is now legally owned and maintained by the archives. After all, we are using our resources to preserve and store it. The question is, who is the legal owner of these documents?

In this case, the documents in question were originals of the inquest of Lydia Brown, who was charged with complicity in the murder of her husband, Robert Brown. As we read in my article a couple of weeks ago, the son, Clarke Brown, confessed to the crime of brutally murdering his father and little sister. He was convicted of the crime and executed by hanging on October 25, 1879. The inquest records for this are held by the Archives of Ontario, as well as being well documented in local newspapers of the time.

In this case, the documents in question were originals of the inquest of Lydia Brown, who was charged with complicity in the murder of her husband, Robert Brown. As we read in my article a couple of weeks ago, the son, Clarke Brown, confessed to the crime of brutally murdering his father and little sister. He was convicted of the crime and executed by hanging on October 25, 1879. The inquest records for this are held by the Archives of Ontario, as well as being well documented in local newspapers of the time.

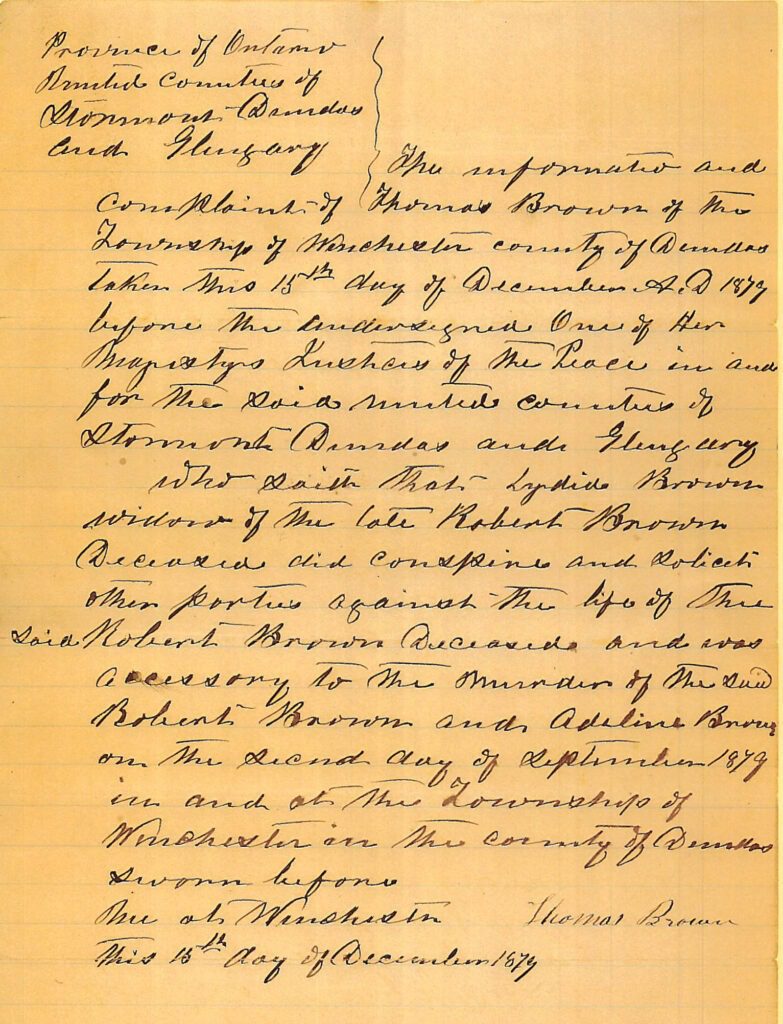

There was a further inquest held in Morrisburg a couple of months later. This was because Thomas Brown officially submitted a written charge to the Justice of the Peace. He claimed that Lydia had conspired and solicited other parties against the life of Robert Brown, and claimed that she was an accessory to the murder.

All that we had previously known about this event was from the local newspapers of the time. The Ontario Archives had no record of this second inquest, however. That was likely because the documents were never submitted to the Department of Justice. Why not? That is the million-dollar question. The original documents of the inquest were not at the Archives of Ontario, because they were sealed in an envelope and placed between the walls of a farmhouse near Winchester. Who put them there? Why were they placed there?

This is anyone’s guess, but, apparently, the house, which was built in 1865, was originally owned by an employee of the court system. Clearly, it was not customary to file original transcripts of an inquest for murder between walls. What would have been the motivation for doing this? Were they a supporter of Lydia Brown, and did they feel it would erase this part of history? Did they think that the documents could be sold to the highest bidder? We will never know the answer to these questions.

All we know for sure is that the package of documents contained the original transcripts of the inquest of Lydia Brown on December 17, 1879. They included the original charge by Thomas Brown, her brother-in-law. The original document is in the file, along with the court seal and signatures. The rest of the file contained the handwritten transcripts of the testimony of those who were called to witness, along with notes and signatures. None other than James P. Whitney had acted as prosecuting attorney. He was a native of Morrisburg who became the sixth premier of Ontario from 1905 until his death in 1914.

The result of the inquest found that the testimony of those who felt that Lydia had plotted the murder of her husband, and even offered to pay someone to assist in the task, were dismissed. The lawyers did not feel that the witnesses were credible. Several testified that Robert Brown was abusive when drunk. This was not mentioned in the newspapers.

In the end, the outcome was that the charges were dropped. Lydia Brown lived out the rest of her natural life with her remaining daughter, youngest Winnifred. But the question remains, why were these inquest documents hidden in a sealed envelope in the wall of a farmhouse? This adds more questions than answers. However, it does all add to the story. It just goes to show you, you honestly never know what will come up for a County Archivist. After consultation with the Archives of Ontario, the original documents will be home in the RG 22-4979, Dundas County Coroner Investigations, and Inquests Collection. Colour copies will be available for researchers to examine at the Dundas County Archives.

dundascountyarchives@gmail.com.