No doubt many of us have felt the frustration or despair of sketchy internet over the last ten months. Since March 2020, kids have been doing a mixture of synchronous online learning, asynchronous learning, which still requires reliable internet, or in-person learning at school when it was safe to do so. People who could have been told to work from home. Virtually every service has been catapulted online, including access to healthcare, banking, and even buying milk. Suddenly, we are demanding a great deal from our internet, out of necessity.

Rural and remote residents are at a distinct disadvantage when it comes to accessibility when compared to their urban counterparts. Unequal access to internet in the city is most often due to social inequalities. Out here, all the money in the world won’t buy you great internet unless you build the infrastructure to support it.

Although we focus on this as a problem stemming from the pandemic, rural and remote regions of Ontario and Canada have had a great deal fewer options for internet than our urban neighbours for many years now. Successive provincial and federal governments have made announcements about a variety of broadband initiatives, but, as the pandemic has shown, we’re not much further ahead.

It was almost twenty years ago that Brian Tobin, then Federal Minister of Industry, established the Broadband Task Force. The aim was to “map out a strategy for achieving the Government of Canada’s goal of ensuring that broadband services are available to business and residents in every Canadian city by 2004.” The Task Force recommended that “All communities should be linked to national broadband networks via a high-speed, high-capacity and scalable transport link.”

Both the Federal and Provincial governments have recently announced increased funding allocated to improve internet access to rural and remote areas. Ottawa has allocated $1.75 billion towards its Universal Broadband Fund, with a goal of 50 Mbps (Megabit per second) download speed, and an upload speed of 10Mbps (50/10) Ontario has recently launched its “Up to Speed: Ontario’s Broadband and Cellular Action Plan.” Ontario’s total spending includes nearly a billion dollars over six years.

So what exactly is broadband, and more importantly, what do we need to do in order for rural and remote residents to achieve acceptable speeds?

Broadband is the transmission of information over multiple radio frequencies. Information through the air. Bandwidth is a measure of how much information you’re sending over a period of time. There are hard limits to how much data you can transmit through the air, which is a function of frequency. You can transmit more data at higher frequencies than at lower frequencies, which is why we are going into 5G. But even at that, there’s only so much data you can send through the air. Our airwaves are very busy. One tech I talked to exclaimed: “Our RF floors are through the roof!”

The internet is essentially many large network servers interconnected by high-speed data trunks. In order to get reasonable service in rural areas, you need to connect to those servers, which are located in urban centres. High speed trunks need to be laid between rural and large urban centres. This means a lot of buried fibre-optic cable between rural and urban areas. The problem with running that much fibre is that it is expensive. We need co-ordination so that any time a road is built, that is a perfect opportunity to bury conduit with fibre in it. We basically have to dig and bury cable, between say Winchester and Ottawa, or tap into existing fibre trunks between Ottawa and Toronto. Back in the 1980s, Bell undertook major projects to install large fibre trunks between large urban centres. Bell owned the infrastructure. Looking to the future, they installed huge amounts of fibre, some of which are still unused. Fibre-optic cable is exactly like wire, except instead of putting electricity through it, you pass light pulses through it using lasers. Fibre-optic cable allows you to send much more data over a single cable than you can with copper wire.

In order to get 50 Mbps in one residence, you can run fibre from a major hub to a central distribution hub, then run copper to individual users. Once you leave the fibre and copper cable, and start running that information through the air, you drastically reduce the amount of information you can send. So, although you hear a great deal about how Broadband is what we need to solve our internet issues in rural areas, it’s a misnomer. Increased broadband is definitely welcome, and absolutely essential for remote areas unable to be tethered physically to the major trunks, but we need more trunks, and more fibre.

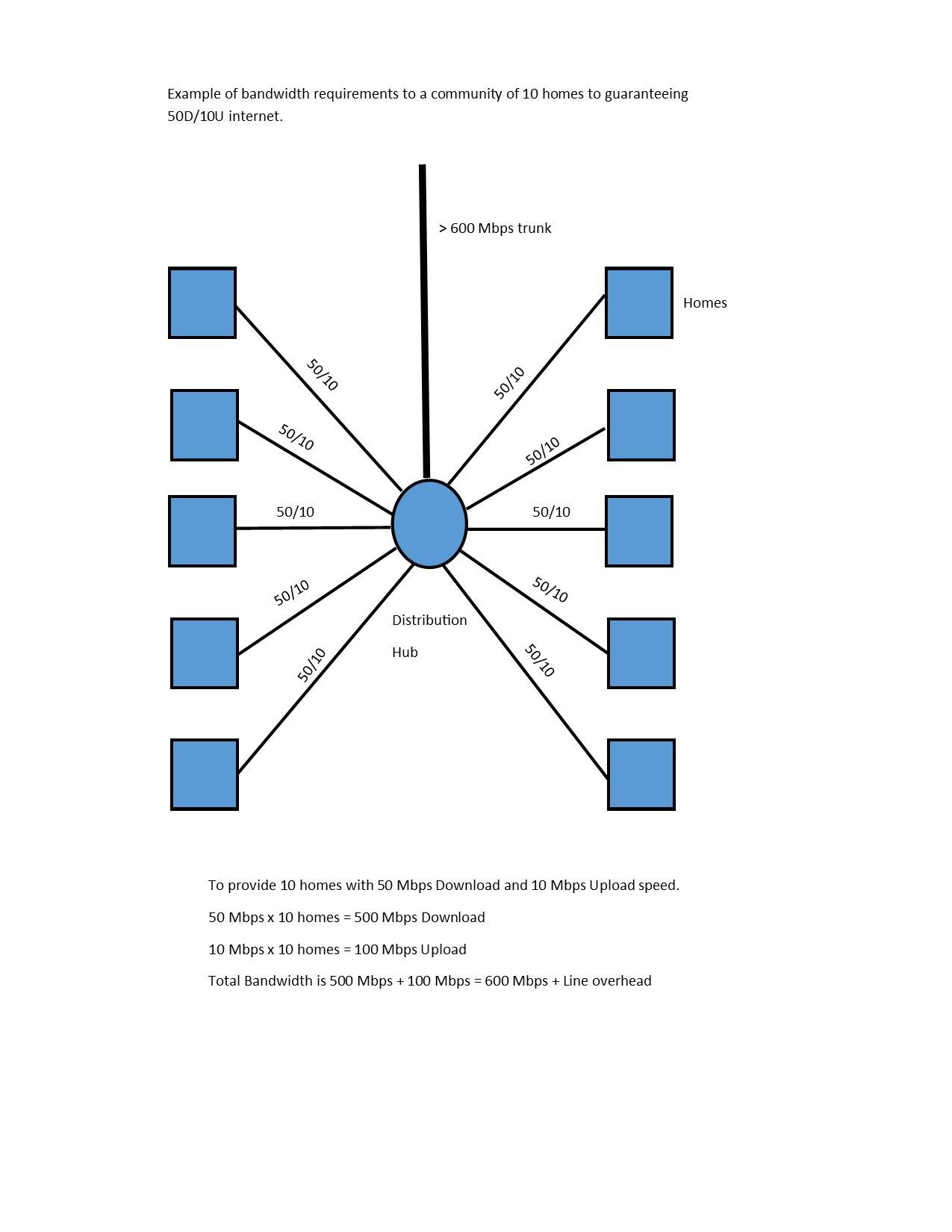

Mbps is essentially a measure of flow rate. Think water. If you want to keep the flow rate up, the size of the pipes needs to increase. If there are ten houses on your street, and you all want 50/10 Mbps, your street has to be equipped with the infrastructure (fibre) to bring in 600 Mbps. If there are ten of those streets in a subdivision, there has to be the quantity of fibre to carry 6000 Mbps to that subdivision. See diagram.

After the pandemic is over, there will most likely be more telecommuting than before, providing the infrastructure is available. This would help green the economy. It is estimated that each worker who shifts to telecommuting means a CO2 reduction of 2450 kilograms a year. Mid-range estimates project, providing we have the infrastructure post-pandemic, that Eastern Ontario could expect to be home to 50,000 telecommuters. That would mean a CO2 reduction of 380 million kilograms each year.

After the pandemic is over, there will most likely be more telecommuting than before, providing the infrastructure is available. This would help green the economy. It is estimated that each worker who shifts to telecommuting means a CO2 reduction of 2450 kilograms a year. Mid-range estimates project, providing we have the infrastructure post-pandemic, that Eastern Ontario could expect to be home to 50,000 telecommuters. That would mean a CO2 reduction of 380 million kilograms each year.