The governments of Canada and Ontario have been sharply rebuked by the Supreme Court of Canada for “what can only be described as a mockery of the Crown’s treaty promise to the Anishinaabe of the upper Great Lakes”. In a unanimous decision in the case of the 1850 Robinson Treaties, the Court ordered the two governments to negotiate a settlement with the communities within the Robinson Superior Treaty within six months of the decision.

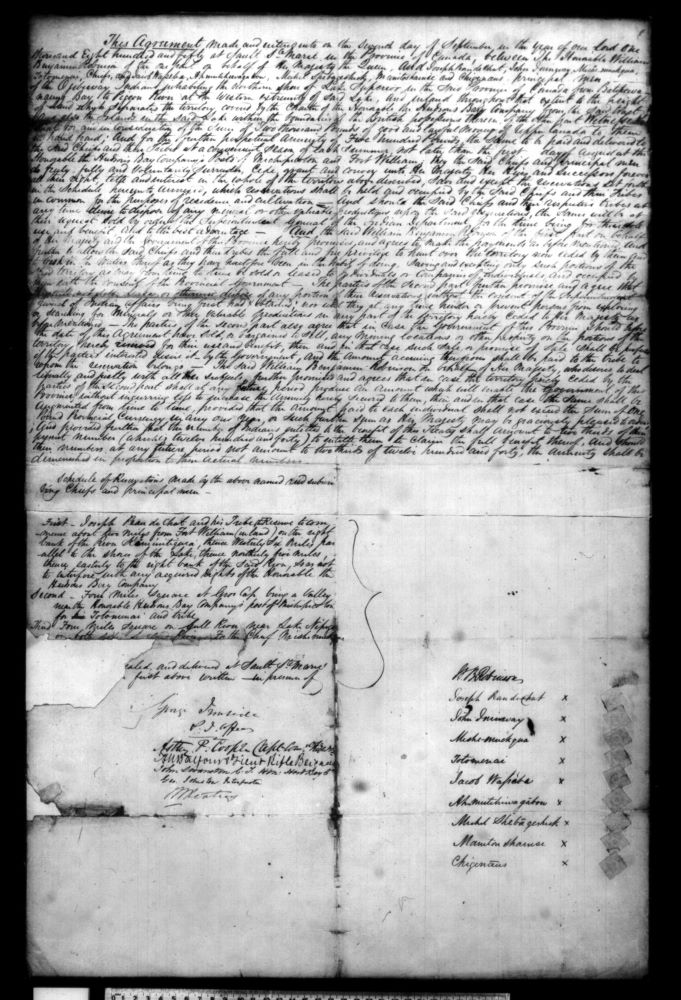

The case involved annuity payments agreed to under the terms of the two treaties, which ceded all the territory north of Lakes Huron and Superior a far as the height of land separating it from the Hudson Bay watershed. The treaty granted the sum of $1 per year to each community member covered by the treaties, with an undertaking that the annuity would be increased: “in case the territory hereby ceded by the parties of the second part shall at any future period produce an amount which will enable the Government of this Province without incurring loss to increase the annuity hereby secured to them, then, and in that case, the same shall be augmented from time to time”.

The amount paid to each individual was raised to $4 per year in 1874, but has remained capped at that figure ever since. The Supreme Court has followed the lead of lower courts that this is a flagrant breach of the spirit and purpose of the treaties, and that Canada and Ontario have to increase the annuity payments. Considering the incredible wealth that has been taken from the territory covered by the treaties since 1850, in timber, fish, copper, gold, uranium, not to mention development of towns and cities in the area, the idea that Indigenous communities were forced to live in poverty and want while being given $4 a year each, makes “a mockery of the Crown’s treaty promise to the Anishinaabe”.

Supreme Court Justice Mahmud Jamal wrote in the decision. “For almost a century and a half, the Anishinaabe have been left with an empty shell of a treaty promise,” as their failure to implement the treaty provisions regarding annuities undermined the spirit and substance of the treaties.

The Court’s decision noted that the Crown has derived “enormous economic benefit” from the land through mining and other activities over the years, while First Nations communities have suffered with inadequate housing and boil water advisories. For 174 years, the Indigenous people of the Great Lakes have been governed as wards of the courts, children in law, subject to the Indian Act and its predecessors, which gave the Crown complete power over Indigenous finances, identity, resulting in confinement to Reserves, total control by non-Indigenous Agents, and a total loss of freedom and sovereignty.

No other ethnic groups have been subjected to legislation like the Indian Act. It has been an act of imperial colonisation comparable only to Apartheid and slavery. When Canada became a Dominion in 1867, jurisdiction over Indigenous affairs and Crown Lands was divided between Canada and Ontario in this province, with the result that the two “Crowns” have constantly played off each other, putting the onus on the other to act honorably towards the First Nations, with each reneging on treaty obligations.

When Canada and Ontario negotiated a compensation agreement with the Robinson Huron people in February, they praised themselves for the deal and then promptly appealed it, seeking to have the other pay the bulk of the $10 billion agreed to. The courts have insisted that the Crown Canada and the Crown Ontario must always act to protect and uphold the honour of the Crown. This both have singularly failed to do in all of their relations with Indigenous peoples. “Failed” may be the wrong word, as it implies that they have tried to do so.

In 35 years of working for and on behalf of Indigenous communities in Ontario and across the country, I have yet to come across a government which has been sincere and showed integrity in dealing with treaty responsibilities. That is an awful fact of Canadian life. And the Supreme Court has acknowledged the truth of that assertion in their decision on the annuity issue. In their decision, the Court instructed the two governments to come with a new annuity amount to be paid, but expressed reservations about the integrity of both. The sum to be decided by the government has to be substantial, they said, but Justice Jamal pointed out that: “The Anishinaabe signatories cannot now be short-changed by the Crown’s sticker shock, which is solely the result of the Crown’s own dishonourable neglect of its sacred treaty promises”. He wrote that simply ordering the parties back to the negotiating table was not sufficient, because it risked forcing the First Nations to rely on a “historically dishonourable” partner to restore the treaty relationship. And they act in our name.