I remember you

by Dr David Shanahan

It’s all about remembering on Remembrance Day, and phrases are used so easily: “Lest we forget”, or “We shall remember them”. These kind of sayings can become just cliches, if we’re not careful. The familiarity of repeating these same words year after year, of seeing the same wreaths surrounding cenotaphs, hearing the same Last Post being played on a trumpet, or another version of Amazing Grace in bagpipes, all of these can be experienced without ever impacting us, except on a temporary and relatively superficial level.

Every year, the Times has a special issue for Remembrance Day, and this is it for 2021. Rather than remaining general, we try and be specific: to give a brief account of individual men who went through the horrors and trauma of war. A photograph, or some individual fact about one of these men, can provide an opportunity to say “I remember you”, the person, and not just the amorphous mass that are represented in the millions of white crosses in foreign graveyards, or the hundreds of thousands of names inscribed on cenotaphs in every community.

To be completely honest, I find the research involved in writing these short biographies to be deeply depressing. So many young men with lives cut short in tragic and horrific ways. Another of the sayings that become cliches is “they shall never grow old”, and we take a strange form of comfort from that. But the truth is that they never got the chance to grow old, never knew life with a lover, with children and grandchildren. They were fed into a system that threw their lives away before they could properly begin.

Not all of them died in the war. Many came home, but not the same people who left. We know about PTSD now, but more than 3,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers were put on trial by their own side for cowardice, desertion, or refusing to “go over the top” one more time. More than 350 were shot at dawn. Very many were simply ill, and some were clearly not guilty of any of the things for which they were killed. Hundreds of thousands came back with wounds that were more than physical, though those wounds were very real. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a veteran who was happy and eager to talk about what they had seen and done “over there”. Some things cannot be put into words, even when the nightmares remain.

This issue, we looked at one short period, around the year 1916, because there are simply too many years, too many names, to cover in one issue. And these individual men deserve a memory. It was a very bad year, as they all were. But 1916 saw the Battle of the Somme. We think of battles lasting hours, even days; but the Somme went on from July until November. Casualties were unbelievably horrendous, but no-one is really sure of exact numbers. Officially, over a million men died on both sides, including 24,000 Canadians. That was just one battle in the four years of catastrophe.

It is right, even essential, that we remember this, and those men who died, were wounded, came home broken. But that is not easy. Our annual memorials are clean: clean uniforms and clean cenotaphs. No veteran who lived through the 1914-1918 war remains to tell us the realities of that time, so we have to make an effort to find out. Soon, the same will be true of 1939-1945. Then all we’ll have left are the little bios, the photographs, the written records.

I’ll be very honest here: I find the whole thing deeply upsetting. I don’t like putting this issue together every year, because I’m never sure if we do the young men justice, not properly. And I’m angry, really deeply angry, that they were put through all of that because three cousins, the Kaiser, the Czar and the King of Britain, put ego and boasting before the lives of their people. Because it wasn’t the War to end War, it just part 1, and part 2 came just thirty years later. More slaughter.

One thing that came out of WWI that was different from other wars: the actual men were remembered in monuments and cenotaphs, not just the generals and the kings. This wasn’t out of a change in their status in society. It was because of the enormous impact that losing a generation of young men had on communities. Young women, parents, and younger siblings kept their memory alive. In the Commonwealth and Britain, this led to Remembrance Day. In other countries, it led to revolution and the downfall of those empires that had sparked the war. By 1919, only the British Empire survived, and it was mortally wounded. The new empires were rising: the United States and Russia. Part two would see them consolidate their positions.

I don’t know. Is this all too little, too late? Can we, should we, continue to remember this way? I have an idea: instead of repeating the moral blackmail of Flanders Fields, with its warning that the dead would not rest if we didn’t remember them, let’s try and pick one man each year to remember. Sadly, there are names on cenotaphs everywhere, including our own community, that have names inscribed for whom there is no information. We know nothing about those men, for some reason.

So, this Remembrance Day, however you mark it, maybe you could pick one of those names and spend the day thinking about them, wondering who they were and who they may have left behind, if anyone. Think of them and say, “I remember you”.

A dedicated man

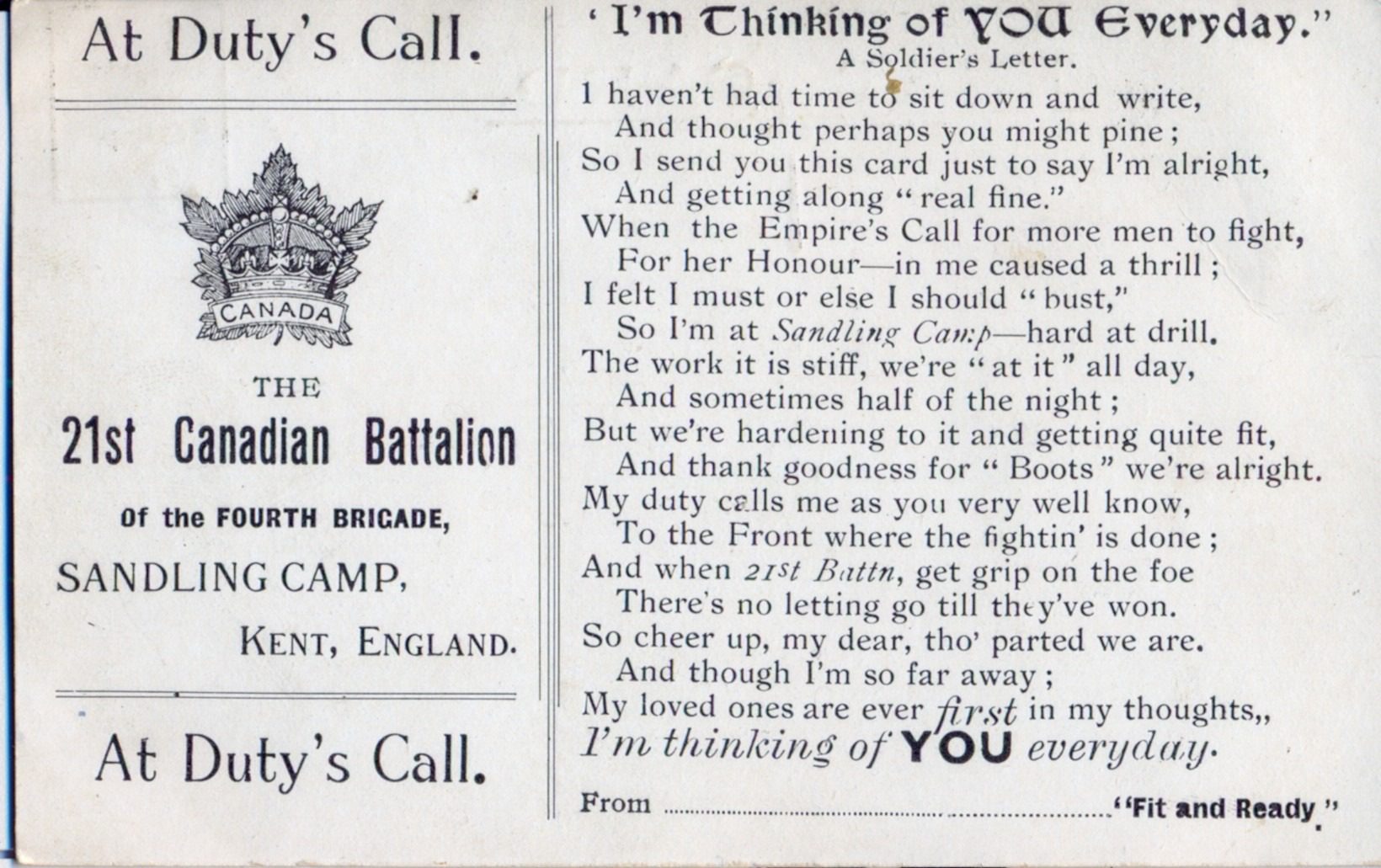

Charles Stonham, 502270

Charles Stonham was born in Sussex, England, on February 7, 1872. He immigrated to Canada and lived in Winchester, where he worked as a miner. When he joined up on January 1, 1916, he was 47 years old, married, with five children. It was unusual for a man of his age, and with his family, to enlist as he did; but a large number of those who joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been born in the United Kingdom, and had been most affected by the Imperialist propaganda of the time. The war was seen as a great Imperial conflict, fighting against what was called an autocratic regime in Germany.

Charles Stonham was born in Sussex, England, on February 7, 1872. He immigrated to Canada and lived in Winchester, where he worked as a miner. When he joined up on January 1, 1916, he was 47 years old, married, with five children. It was unusual for a man of his age, and with his family, to enlist as he did; but a large number of those who joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been born in the United Kingdom, and had been most affected by the Imperialist propaganda of the time. The war was seen as a great Imperial conflict, fighting against what was called an autocratic regime in Germany.

Charles arrived in France on May 20, 1916, as part of the 9th Field Company of the Canadian Engineers, but was taken seriously ill in January, 1917. The cause was Nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys. He had suffered an attack previously, in 1906, but had recovered after two months. The medical report in 1916 noted that his condition was an old one “slightly aggravated by service” in the trenches. As a Sapper, Charles was probably engaged in digging trenches and tunnels, which led to him suffering from constant headaches and dizziness.

It was thought that recovery could take three months without further treatment, and he was returned to Canada in July, 1917, declared unfit for active service. His discharge from the army came in June, 1918. He and his family moved to Kingston, where Charles died in March, 1944.

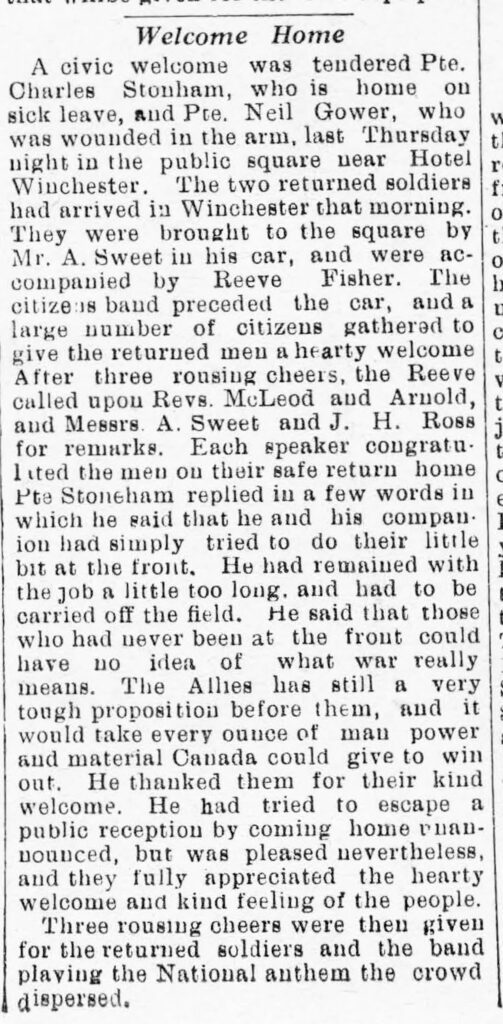

Charles Stonham signed up as a 47 year-old husband and father of five. Eager to do his bit, as they called it, he left everything behind him to go to France and be part of the crusade for Empire. On his return from France, he was given a civic reception in Winchester, as the accompanying newspaper clipping describes.

Dundas in the Boer War, 1899-1902

The Boer War was the first foreign war to which the nation of Canada sent troops. It was the first time that Canadians distinguished themselves in a foreign battlefield. It also showed how Canadians could stand apart from the British Empire. Canada did generate a great atmosphere of patriotism, judging by the newspapers of the time, including newspapers in Dundas County.

Canada sent several contingents to South Africa. The government uniformed them, trained them, provided supplies, horses and transportation. The cost of this endeavour was close to three million dollars, a huge investment for the time. Almost 7,000 troops left, including 12 nurses. 270 of these soldiers did not return. The number of horses who did not return was very high.

Twelve men volunteered and served from Dundas County. John Major was born and raised in South Mountain. He had joined the effort after he had attended a military school in Toronto and, in October, 1899 enlisted in the First Contingent. He saw service in South Africa and returned home in November, 1900. In 1902, he returned to South Africa for a second mission.

William Van Allen, a native of Vancamp and Mountain, enlisted in the 3rd Canadian Mounted Rifles. Isaac Shea was a resident of Winchester when he enlisted in the second contingent. Alexander William Munro of Chesterville was a member of the 4th Contingent. Matthew Carlysle, while a native of Morewood, was actually in the Canadian West when he enlisted in the 4th Contingent. However, by the time he arrived in South Africa, the hostilities had ended, so he did not see action.

S. M. Liezert enlisted in 1901 in Cranbrook, British Columbia, but after returning from the war, settled in Vancamp. He served at the end of the war. A. E. Ault served with the Royal Canadian Dragoons and saw action in 44 engagements. James George Stephenson of Morewood, unfortunately, did not survive. After a year in the war zone he succumbed to enteric fever. The residents of Morewood have erected a monument in memory of him.

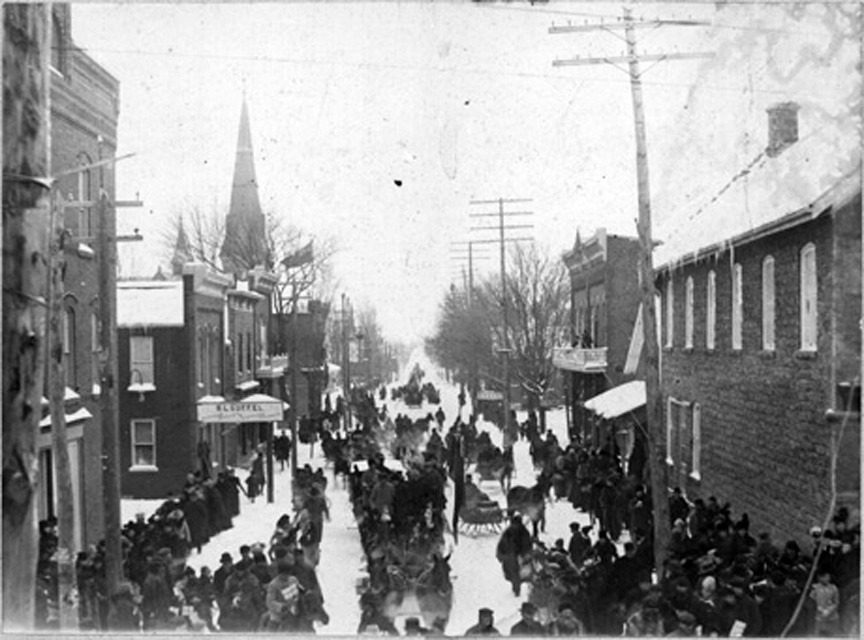

Finally, Lorne Mulloy had enlisted from Ottawa, but was born in Mountain Township, and educated in schools in Morrisburg and Iroquois. Mulloy became the hero of the nation when he returned from the war, blinded in battle. When he returned to Winchester in December, 1900, along with Isaac Shea, a huge parade took place to honour them. He began a journey of lecturing to large crowds about his experiences in the war and instilling an aura of patriotism. In his words, “patriotic hearts beat strong and high”. This continued for the remainder of his life.

Private Frank David Valentine, 633384

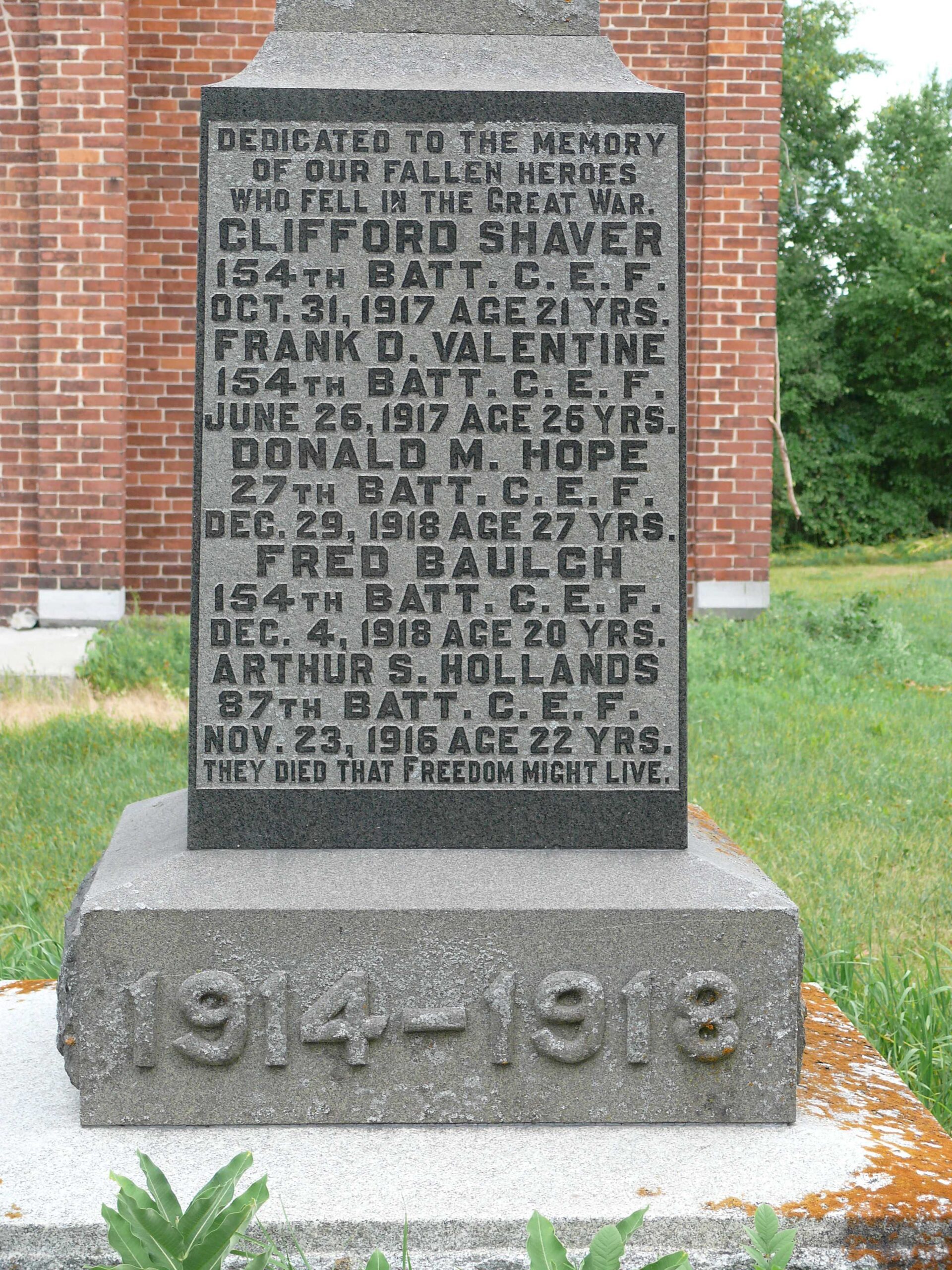

Frank Valentine was born in Aberdeen, Scotland on New Year’s Day, 1891 and came to Canada in 1910. He lived in Mountain, where he became involved with the Mountain Red Cross, the Odd Fellows, and worked as a farmer. He enlisted at South Mountain on February 1, 1916. After the usual training, Frank embarked on the S.S. Mauretania on October 25, 1916 with the 38th Battalion. He was appointed Acting Lance Corporal while in England, but reverted to the rank of private when he arrived in France in May, 1917. He joined his unit at the front on June 11 and was killed in action on June 26, 1917 during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, after just two weeks in the field.

Frank Valentine was born in Aberdeen, Scotland on New Year’s Day, 1891 and came to Canada in 1910. He lived in Mountain, where he became involved with the Mountain Red Cross, the Odd Fellows, and worked as a farmer. He enlisted at South Mountain on February 1, 1916. After the usual training, Frank embarked on the S.S. Mauretania on October 25, 1916 with the 38th Battalion. He was appointed Acting Lance Corporal while in England, but reverted to the rank of private when he arrived in France in May, 1917. He joined his unit at the front on June 11 and was killed in action on June 26, 1917 during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, after just two weeks in the field.

Frank has no known grave, and is remembered on the Vimy Memorial, along with the 11,000 Canadian soldiers who were listed as “missing, presumed dead” in France.

Roy Austin Cassidy, Private, 177511

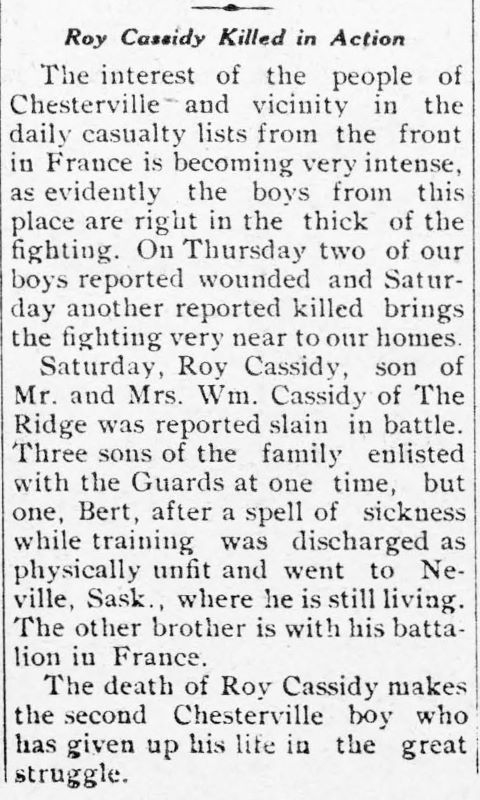

Roy Cassidy was one of three brothers from RR#3, Chesterville, who signed up during WWI. Roy Austin Cassidy was born in Kemptville in 1895, and was a farmer on RR #3, Chesterville. Like many of his neighbours of the same age, he joined up on November 11, 1915, an ironic date, and was posted to the 87th Battalion, Canadian Grenadier Guards.

He arrived in England aboard the Empress of Britain, and then spent weeks in hospital there, for various problems. Hospitalized with Gastritis in February; with Mumps in March-April; and Measles in May, 1916, before, finally, he went to France on August 13, 1916. Roy didn’t survive for long. He was killed in action, September 8, 1916.

A notice appeared in the local newspaper on September 21, noting that: “Mr. And Mrs. Wm Cassidy are in receipt of very sympathetic letters of condolence from General Sir Sam Hughes and from the premier, Sir Robert Borden on the death of their son, Roy, in the recent fighting in France.”

Roy was remembered at a “very interesting service” in Trinity Methodist Church, when the congregation were encouraged to live up to “their responsibility in the matter of recruiting if Canada’s promise of half a million men is to be redeemed… Feeling reference was made by the pastor to the death in battle of Pte. Roy Cassidy and as a token of respect the congregation stood with bowed heads while “The Dead March in Saul,” was rendered by the organist”.

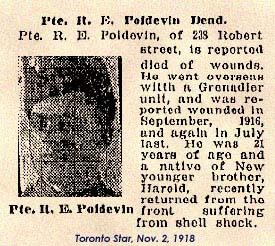

Private Robert Edward Poidevin, 177514

In the same newspaper that reported the death of Roy Cassidy, there was a notice stating that “The name of Pte. R . E. Poidevin is among the wounded in this morning’s casualty list.” Robert Poidevin was a neighbour of Roy Cassidy in Chesterville, and the two young men had joined up on the same day, November 11, 1915, travelled to England on the same ship, the Empress of Britain, and shared the same experiences of soldiering.

But, whereas Roy Cassidy had lasted just a few weeks in France before being killed, Robert Poidevin would have a longer, but no less tragic life in the trenches. He was wounded by shrapnel in his foot and thigh in September, 1916, just three months after arriving in the trenches in France. After recuperating in Liverpool, he returned to the front. He spent another two months in hospital in 1917, for an infection, before again returning to the front.

In July, 1918, he was involved in an unusual accident, when digging trenches. A fellow soldier in the trench accidentally hit him on the hand with a pick, and Robert was back in hospital once again. An investigation concluded that the wound was accidental, and not an attempt to avoid time in the trenches, and, to underline this, Robert was appointed Acting Corporal on August 31, 1918. But time and luck was running out for Robert Poidevin, and he was fatally wounded in action on September 27, 1918.

Robert had listed his next of kin  his sister, Hazel, who lived in Toronto, as did his brother. It may be that the family lived there at the time. As a result, the Toronto Star noted his death in November, 1918, and reported that his brother, Harold, had recently returned from the front suffering from shell shock.

his sister, Hazel, who lived in Toronto, as did his brother. It may be that the family lived there at the time. As a result, the Toronto Star noted his death in November, 1918, and reported that his brother, Harold, had recently returned from the front suffering from shell shock.

Two men with lasting injuries

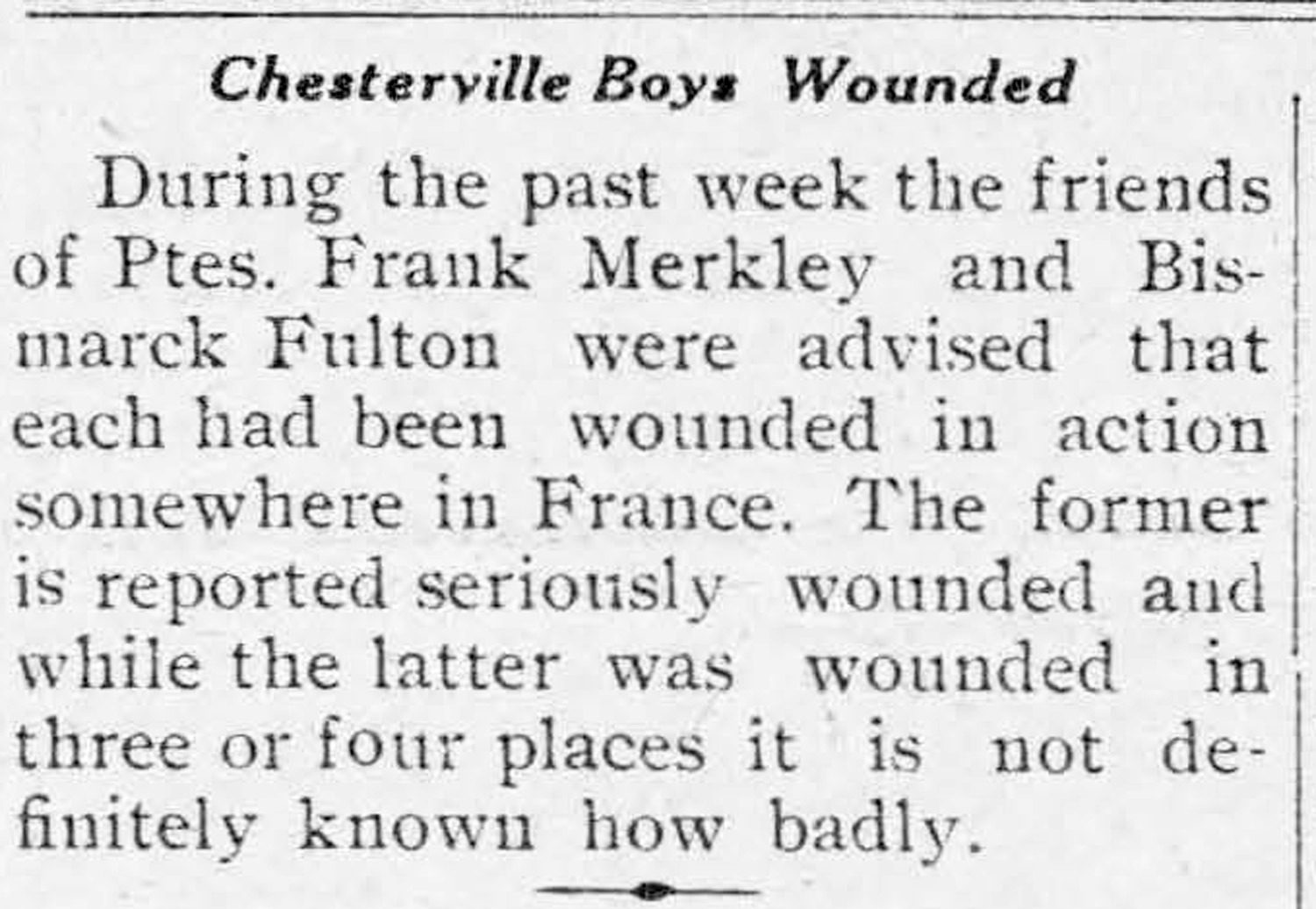

A paragraph in the Recorder on September 21, 1916 reported that two friends from Chesterville had been wounded in France. Frank Merkley and Bismarck Fulton were well known in the area, and the report stated that Frank was seriously injured, while Bismarck had been wounded in three or four places, though it was not known how bad his in juries were. The Service Records of the two men throw more light on their stories.

Private Frank Merkley, 177343

Frank Merkley worked as a barber in Chesterville, and married to Ethel. Born in 1881, Frank joined up October 27, 1915, when he was already 34 and a half years old. After training, he arrived in France on June 18, 1916. His time at the front was not long, but it had a devastating impact on him.

Frank was wounded in the arm by shrapnel on September 2, 1916. The medical report on his injuries showed that they were, as the newspaper report had said, serious. He had been shot in the right arm, between the shoulder and elbow, resulting in a loss of function to his elbow and partial paralysis of his right hand. The medical report was blunt: “Hand useless”. Frank sailed back to Canada on February 25, 1917, and was declared unfit for military service in Quebec.

Frank Merkley was discharged from the army on July 31, 1917. He died on October 17, 1966.

Bismarck Earl Fulton

Born in Chesterville, 1895, Bismarck Fulton was a farmer who joined up on November 17, 1915. Originally assigned to the Canadian Grenadier Guards, he was later transferred to the Canadian Engineers after being wounded in the head and side by shrapnel on the Somme, September 5, 1916. He spent four weeks recuperating in hospital in England.

He was wounded again in 1917, and after recovering from that, was transferred to the Canadian Light Railway Operating Company on November. After being appointed Lance Corporal in June, 1918, Bismarck was gassed the following month and was again hospitalised. But the effects of the mustard gas were still impacting him and in December, 1918, he was transferred to Seaford, England, where he remained for the rest of the war. Bismarck was discharged, January, 1919.

Bismarck was a strange name to carry into battle against the German Empire, and his experiences in France left him permanently affected by the wounds and the effects of mustard gas. Records show Bismarck Earl Fulton marrying Ada Keen in Drumheller, Alberta, in 1923, and dying in Vancouver in 1970.

Private Norman Earle Bush, 639411

Norman Bush was born in South Mountain on March 4, 1897, son of Theodore Bush. Norman was a labourer who joined up in Merrickville on January 21, 1916 when he was 18 years old. There was no height requirement at the time, as Norman stood just 5 ft. 2½ inches tall. The link with Merrickville was through his grandmother, Melissa Briggs, who had been his foster mother growing up. Norman named her as his beneficiary in his will, drawn up before he was sent to France on May 1, 1917.

There were usually some small details recorded in the files that give some personal insight into these young men. Norman is described as having feet that were “slightly flat”, and with ringworm scars on his face between his ear and eye.

Norman arrived in France on May 24, 1917 and was transferred to the 2nd Battalion of the Canadian Infantry Regiment, arriving in the trenches on June 27. Just less than three months later, Norman was killed in action near Rouen. His battalion was due to be relieved that night, but somehow, Norman died before he could leave the front. He is buried at Aix-Noulette Communal Cemetery Extension, Pas de Calais.